Git - pull requests

In the last article, we learned about creating new branches—first local branches (with branch -b) and then on the server (using git push). A few questions remained opened—the first is about updating the branch. Let’s say we split from the master to a branch called develop. In the meantime, someone else updated the master. So how do we update? There are a few ways to do this. The easiest way is to pull from a branch using pull.

What does that mean? Says there’s is a remote repo, and then there’s our local version. On our local version we made some changes, and on the remote version someone else made changes (or more accurately, made changes to locally and pushed them to the server). Now we want to update our version. If we run push and there are no conflicts, then everything is OK. If we run git push origin master and there are conflicts, we get an error saying we have conflicts with the source. Just for this we can use:

git pull origin master

What’s going on there? git pull you know already. The origin is the name of the remote server as it’s usually called, and master is the name of the branch.

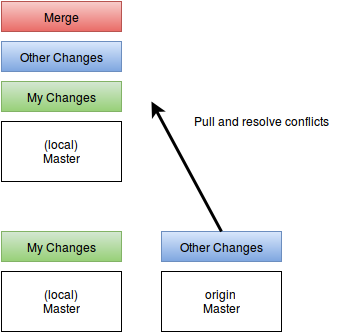

Immediately, all of the commits made to the remote server are pulled to our local machine and if there are conflicts they are displayed just like in SVN. We’ll have to resolve all the changes (again, just like SVN) and afterward run commit and add to the changes that are considered changes to the code. How does this look? Just like this:

Pulling changes made from someone else’s changes. Resolutions to the conflicts are made on our local branch.

Each time I pull code, the remote commits are pulled to my branch placed on my changes. If there’s a conflict, their resolution is placed on my commit and on the remote commits. Then I need to run git put origin master, and the push is received.

If I run git pull origin master before I push and there are conflicts, I won’t need to resolve them, but if I run push, in the log I’ll see that I have an empty commit. So the question is why? The answer is that when I run git pull, I always bring not only the changes from the remote server, but also do a merge and that must be recorded in the log, even if there’s no conflict. There is a way to avoid this which is called rebase. We’ll cover it in the next article.

And so, if we know how to pull a repo from a remote location, make changes, update it regularly, and also to push changes to the master, then the time has come to know this all looks in the real world. You should never, and I mean never, push code straight to the master or the develop, or any other main branch. All of the changes made to the main branches are done via pull requests.

How is this done? Let’s say I have a master branch which is the main branch and I want to add a new feature. I’ll open the master locally using clone or (if I have the master on my computer) I’ll update it using pull. Afterward, I create from it a branch using checkout -b. I make the changes in the code for the feature, and push them as a remote branch. If I have GitHub, using the GUI, I make a pull request. If I’m working with a different system (like stash) I make the pull request using that system. Whoever has the write permissions for the master branch checks the code and can raise any concerns they may have. Then, I can fix things (and push the changes to the same branch of course) and once everything is ready, the pull request is approved and the version is merged with the master.

The pull request is always done through the system that is managing Git and is always done with a GUI. In the pull request, it is common practice to write exactly why it was made and which changes were made in the code. Generally, you can also see the changes between files in the system. These systems are very convenient to work with when working on open source projects.

In the next article, we’ll look at rebase and how it’s significantly difference from git pull.

Next up, we’ll look at merging and splitting different branches.

About the author: Ran Bar-Zik is an experienced web developer whose personal blog, Internet Israel, features articles and guides on Node.js, MongoDB, Git, SASS, jQuery, HTML 5, MySQL, and more. Translation of the original article by Aaron Raizen.

Recent Stories

Top DiscoverSDK Experts

Compare Products

Select up to three two products to compare by clicking on the compare icon () of each product.

{{compareToolModel.Error}}

{{CommentsModel.TotalCount}} Comments

Your Comment